The Christian Year: An Introduction

What is the Liturgical Year or Church Year or Christian Year?

How Can It Make A Difference in Your Relationship with God?

by Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2011, 2021 by Mark D. Roberts

Happy New Year in Late November?

Has anyone ever wished you a happy new year…in late November? That has happened to me several times recently. Even though I know what’s going on, it does feel rather strange.

If you’re a member of a highly liturgical church, such as Catholic, Episcopal, or Lutheran, what I’ve just said makes sense. (If you’re Eastern Orthodox, you think I’m three months behind the time.) But if you’re not involved in such a church, I had better explain what I’m talking about.

The Christian year, sometimes called the church year or the liturgical year, is a centuries-old way that many Christians have ordered the 365-day year. It depends, not on the positions of the sun and moon, nor on the start and end of school, nor on the requirements of the IRS, but rather on key aspects of the life of Christ that are coordinated with the solar calendar. The major holidays (literally, holy days) in the church year are Christmas (December 25), Good Friday and Easter (in the spring, dated according to Jewish Passover), and Pentecost (seven weeks after Easter). Every other special day or season fits around these crucial days (Advent, Epiphany, Ash Wednesday, Lent, Palm Sunday, Holy Week, Maundy Thursday, etc.).

When I have taught worship leaders from around the country, I have often asked about their awareness of the liturgical year. It used to be that the vast majority had little or no knowledge of it, apart from the big holidays, Christmas and Easter. If they had any sense of the liturgical year, they assumed that it was something for Catholics and other high church folk, with little relevance for the rest of us. I can understand this perspective because I was raised in a church that recognized Christmas, Palm Sunday, Good Friday, and Easter, but that’s about it. I had always assumed that things like Lent were for my Catholic friends. And since Lent seemed to involve some sort of fasting, I was happy to leave it well enough alone. Give me the feasts, I reasoned. Leave the fasts for the Catholics and Jews. (I didn’t have any sense of Ramadan back then.)

It wasn’t until I was preparing for ordained ministry that I gained some exposure to the Christian year. I learned – much to my surprise – that many Presbyterians and other Protestants take this stuff quite seriously. For the first time in my life, I heard a Presbyterian pastor get excited about the benefits of the church year for corporate worship and private devotions. I was curious, though I didn’t quite get his enthusiasm. What difference would the liturgical year make in my life? The answer seemed to be: none at all.

When I became the Senior Pastor of Irvine Presbyterian Church in 1991, the church had a history of recognizing more of the liturgical year than I had acknowledged before. During my sixteen-year tenure there, I grew to appreciate the richness that such a perspective can bring to the worship life of a church, as well as to my own devotional life. The truth is, all kidding aside, that I actually began to experience the first Sunday of Advent (in late November or early December) as the beginning of a new year.

Today, though I am no longer a parish pastor, I can feel the flow that begins with Advent and carries me through the birth of Jesus to his death and resurrection, and beyond that to the sending of the Spirit and the celebration of Christ’s kingly reign. Believe it or not, there’s a sense in which early December begins my preparation, not just for Christmas, but also for Easter. I know this may sound odd to you, even esoteric and weird. But I’ve found that recognizing the Christian year has enriched my faith in many ways. I’d like to share some of these with you.

Now, let me hasten to add that nothing in Scripture demands recognition of the church year. We do not have in the New Testament some equivalent to Leviticus 25, where God lays out for Israel the major fasts and feasts during the year. So, although the liturgical year is structured around the biblical story of Jesus, it is not commanded in Scripture in the way of the Jewish holidays for the Jews. Of course, Christians aren’t commanded to celebrate Easter or Christmas in the way we do either. The church year, therefore, is not something all Christians must observe, or must observe in exactly the same way. (In fact, Eastern Orthodox believers have a different pattern throughout the year and even celebrate Easter on a different day!)

Nevertheless, I believe that an awareness of the liturgical year can enrich our worship and therefore our relationship with God. In fact, when I’ve taught on this subject to worship leaders who have very little idea of what I’m talking about, they have come away excited about the potential for their churches.

Overview of the Christian Year

Advent wreath in my home

All versions of the Christian year, to my knowledge, recognize Christmas and Easter as the twin hubs around which rotate a wide variety of feasts, fasts, and seasons of the year. But, even the specific dates for Christmas and Easter vary among different Christian traditions. So, the Christian year I’m going to describe is a version of the Western tradition, which you’ll find in many Protestant denominations, as well as the Roman Catholic Church.

I want to provide an overview of this year in case you are not familiar with it. Before I do this, however, I should say that there is not one, universally-recognized version of the Christian year. In fact, you’ll find variation in timing and practices, sometimes even within one denomination or tradition. For example, many Presbyterian churches use purple as a primary Advent color, while other Presbyterian churches use royal blue, and other Presbyterian churches decorate their worship spaces with secular Christmas colors of red and green without paying much attention to Advent. None of these choices is necessarily wrong or right, though, as you may guess, I would encourage any church to recognize Advent and be enriched by its themes. Color schemes are clearly secondary in importance.

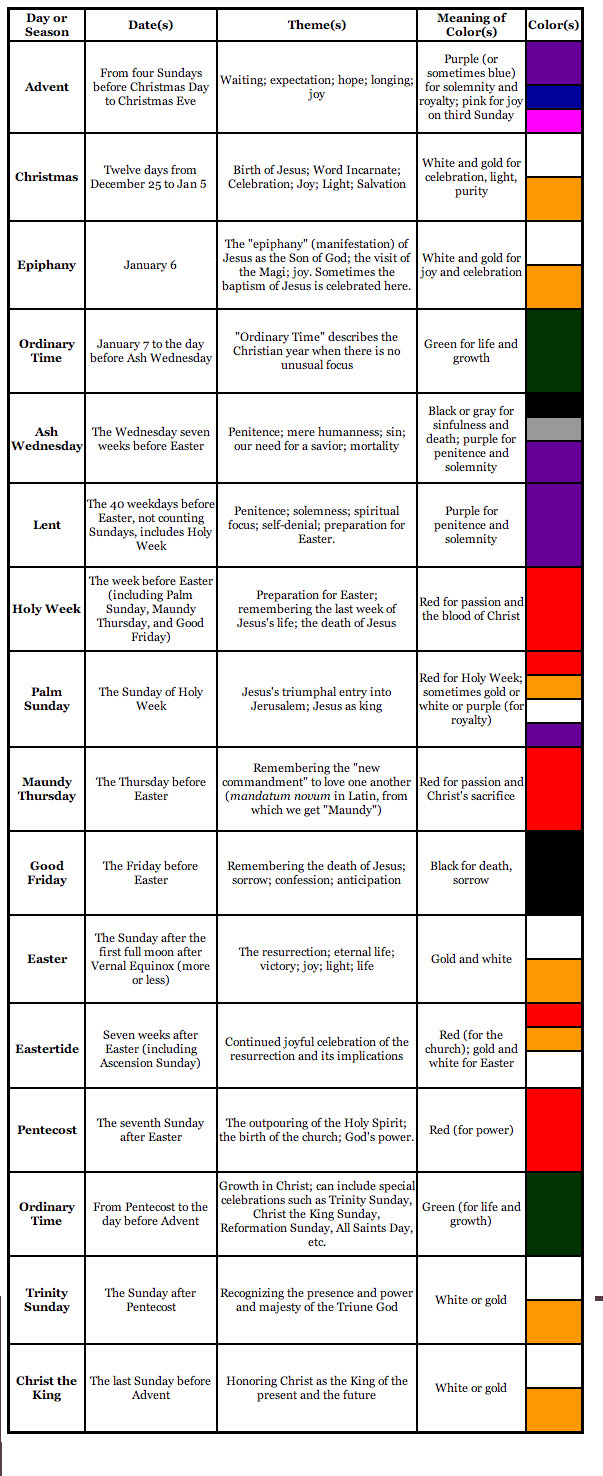

Here’s a summary of the basic days and seasons of the church year, along with some of the main themes:

Advent

When: Begins four Sundays prior to Christmas. Includes all days until Christmas (or Christmas Eve). Length varies according to the date of the first Sunday. The beginning of the Christian year.

Themes: Waiting; Expectation; Hope; Yearning; Our need for a Savior. A minor theme of joy. Christians remember the Jewish yearning for the “advent” (from Latin for “coming” or “visit”) of the Messiah. We also get in touch with our hope for the Messiah’s second advent.

Christmas

When: December 25th through January 5, a twelve-day season. Many Christians begin celebrating Christmas on Christmas Eve. Of course, most people think of Christmas as a day, not a season. But, as the song narrates, there are twelve days of Christmas.

Themes: Celebration of the Incarnation of the Word of God; Salvation; Joy; Kingdom; Peace; Giving.

Epiphany

When: January 6, the day after the season of Christmas.

Themes: Some traditions emphasize the visit of the Magi (Wise Men) and the universal import of salvation in Christ. Other traditions focus on the baptism of Jesus.

Ordinary Time

When: Times during the year when there is not a special day or season. Ordinary time begins the day after Epiphany and extends until the day before Lent (Mardi Gras, Fat Tuesday). Ordinary time begins again after Pentecost, extending until the day before Advent.

Themes: Ordinary time is not “plain, boring time,” but rather “counted” time. Different traditions include many celebrations during ordinary time, such as Trinity Sunday, Christ the King Sunday, All Saints Day, and so forth. The themes of ordinary time include the basic elements of the Christian life.

Lent

When: Forty weekdays prior to Easter, beginning with Ash Wednesday. The precise dates vary according to the date of Easter, which can range from March 22 to April 25. The six Sundays during the season of Lent are not counted in the forty days.

Themes: Penitence; Morality; Human Limitations; Need for a Savior; Self-Denial; Preparation for Good Friday and Easter. Some Christian traditions emphasize Lenten fasting (from food and other delights). Other traditions focus on adding spiritual disciplines.

Holy Week

When: The last seven days of Lent, prior to Easter. Holy Week includes: Palm Sunday (Passion Sunday), Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday.

Themes: The last week of Jesus’ life; The death of Jesus and its meaning; Love for one another (Maundy Thursday). Palm Sunday celebrates Jesus and king, but leads into a solemn preparation for remembrance of his death.

Easter

When: A fifty-day season of the year, beginning on the evening before Easter and continuing for seven Sundays until Pentecost. Includes Ascension Day. Easter Sunday or Resurrection Day is celebrated on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the Spring equinox (March 21). (The Eastern Orthodox Easter occurs a week later.)

Themes: Salvation; Victory; New life; Joy; Christ reigns.

Pentecost

When: The seventh Sunday after Easter.

Themes: The outpouring of the Holy Spirit; The birth of the church; Power for service in the church and the world; The inclusion of all of God’s people in ministry. “Pentecost” comes from the Greek word for fifty, from the phrase “fiftieth day [after Easter].” In some traditions it is called Whitsunday (White Sunday), perhaps owing to the white garments of those baptized on this Sunday.

Ordinary Time (again)

When: From the day after Pentecost through the day before Advent, about five months.

The Eastern Orthodox Alternative

The Orthodox year begins in September and includes several feasts and fasts that are not part of the Western Christian year. For example, what Western Christians call Advent, for Orthodox Christians, is called the Christmas or Nativity Fast. It begins on November 15 and is a 40-day season of serious fasting in preparation for the 12-day season of Christmas.

The Colors of the Christian Year

Part of what makes observing the liturgical year special is color. Different events and seasons are reflected in a variety of colors, including purple, white, green, black, red, pink, blue, gold, and some other colors as well. The seasonal color, usually displayed in various ways in the place of worship, reflects and augments the thematic elements of the season. So, for example, because purple is understood to symbolize penitence (among other things) it is used during the season of Lent.

Once again, I should emphasize that there is no single color scheme either recognized by or imposed upon all Christians. In the twelfth century, Pope Innocent II systematized the Roman Catholic color scheme, but since Vatican II in the 1960s, Roman Catholic churches have exercised some freedom in their use of alternative or additional colors. In recent years, many Protestant churches have moved from using purple in Advent to using royal blue. This move reflects a variety of motives, depending on the congregation. For the most part, it seems to be an effort to distinguish Advent from Lent. Blue continues to symbolize royalty and solemnity. Some churches connect blue with the color of the night sky or as a symbol of creation. A compromise popular in some congregations is the use of purplish-blue in Advent and a reddish-purple in Lent. Such freedom in the use and interpretations of color can allow for innovation and distinctive celebration, though it can also be a bit confusing.

If you’re looking for a more in-depth examination of the church year, I would highly recommend an outstanding website: The Voice: CRI Institute. Their material about the church year is top-notch.

The chart below is my attempt to reflect what seems to be a consensus among many churches. I will identify the day or season, along with calendar dates, themes, and common colors.

Liturgical Colors and Visual Art in Worship

The use of color and visual art in worship is nothing new. For centuries, the Roman Catholic church incorporated elaborate artistic works in its sanctuaries. But, with the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, and especially in the Reformed branch of the Reformation (my theological tradition), the perceived excesses of Catholic art in worship led to the virtual excommunication of visual art from worship. Visual symbolism in Reformed churches was minimal (cross, pulpit, baptismal font) and modest.

This artistic minimalism continued to be the dominant force in most evangelical churches in the United States, though some mainline Protestant churches developed visual traditions along the familiar lines of the Roman Catholic tradition.

In the last decade, however, many churches throughout the Western world have “discovered” the power of the visual in worship. Owing partly to the pervasive influence of visual imagery in our culture, partly to the cross-pollination between different streams of Christian tradition, and partly to the power of digital projection, churches that would never have considered the use of visual art in worship have not only begun to use it, but even to major in it. Many large evangelical and charismatic churches, the kind that only twenty years ago would have incorporated only words and music in worship, have even hired staff whose primary responsibility is to provide stunning visuals for liturgical purposes (though they would avoid the word “liturgical” in favor of something like “celebrative” or “worshipful”).

I believe that, for the most part, the rediscovery of visual art in worship is a positive development. Yet some churches have set off on the journey of liturgical art as if they were groundbreaking pioneers, rather than pilgrims traveling along a well-worn path. These churches might do well to look into the use (and occasional misuse) of visual art in Christian history. We all have much to learn from the centuries of Christian worship that precede us. Or, to use a different metaphor, we who are beginning to utilize the visual in worship might just find in Christian tradition a treasure trove with gems just waiting to be used afresh.

In my opinion, the colors of the Christian year are part of this treasure trove. The intentional use of colors and color changes in worship spaces can enliven and deeper our worship, as well as add to the beauty of the experience. Colors can symbolize truth. Colors can delight the eyes. Colors can move the heart. Colors can suggest and symbolize and hint in a way that words cannot.

Let me give just one example among many from the worship in Irvine Presbyterian Church, where I served as senior pastor of sixteen years. One of the most striking aspects of the worship space in this church is the cross at the front of our sanctuary. Its simplicity and power convey symbolically and emotionally the truth of the Gospel. During my tenure as pastor, along with the members of my congregation, I meditated upon this cross many times, remembering what Jesus did for me. It impacted both the depth and the passion of my worship.

The cross stands alone, not as a decoration, but as a simple image of salvation. We never hung anything from the cross, except for one day of the year: Good Friday. Early in the morning of Good Friday, somebody draped a basic black cloth over the horizontal bar of the cross. I knew in advance that this would be there. I was not surprised to see it. Yet, every year, when I entered our sanctuary on Good Friday and saw the black drape, my heart was struck. For some reason that black cloth hanging on the cross brought home to me the horror and the wonder of Jesus’ death. I often found myself brought to tears by that compelling yet basic symbol.

The cross stands alone, not as a decoration, but as a simple image of salvation. We never hung anything from the cross, except for one day of the year: Good Friday. Early in the morning of Good Friday, somebody draped a basic black cloth over the horizontal bar of the cross. I knew in advance that this would be there. I was not surprised to see it. Yet, every year, when I entered our sanctuary on Good Friday and saw the black drape, my heart was struck. For some reason that black cloth hanging on the cross brought home to me the horror and the wonder of Jesus’ death. I often found myself brought to tears by that compelling yet basic symbol.

This is just one example among many possibilities from my personal experience. It illustrates, I think, the potential power of color to motivate and shape our worship. I know that some of you will relate immediately to what I’m saying because your experience is similar. Others of you will understand what I’m describing, but it isn’t something you yourself know in a personal way. Some of my readers will no doubt wonder if the use of color is consistent with biblical teaching. My response to this concern would point to God’s good creation of a colorful world. I would also underscore the colors of the Tabernacle in the Old Testament, not to mention the brilliant colors of the new creation as seen, for example, in Revelation 21. Surely a God who has created such a wide spectrum of color would welcome our use of his colorful creation to worship him.

Speaking of worship, tomorrow I’ll say a bit more about how paying attention to the Christian year can enrich our worship. Stay tuned . . . .

The Christian Year and the Textures of Worship

As Christians, we worship in light of the Gospel. Our worship is a response to the God who has reached out to us in Jesus Christ, saving us from sin, death, isolation, and meaninglessness. Thus, Christian worship is consistently infused with joy and gratitude. Moreover, since we worship the King of king and Lord of lords, we approach God humbly as well as boldly. And because God is glorious and majestic, our worship is filled with praise.

At the core and in many of the details, Christian worship from day to day, from week to week, and from year to year, is essentially the same. If we ever stop worshiping the one true God, if we ever stop responding to God’s love given in Jesus Christ, if we ever stop offering ourselves to God in gratitude and love, then we’ve lost the core of worship. But this is not to say that our worship should be monotonous and monochromatic. In a given worship service, we might focus on one particular aspect of God’s nature and therefore utilize distinctive expressions. We might, for example, focus on the holiness of God, praising God’s perfection, thanking him for the gift of the Holy Spirit, and asking God to finish in us his work of sanctification (making us holy). In another service, we might emphasize God’s grace, focus on the Lord’s forgiveness, and seek help to be gracious with one another. And so forth and so on. When our worship responds to the multifaceted character of God, and especially when it is shaped by the diversity of biblical revelation, it will have different textures and colors, even though the basic fabric is consistent from week to week.

The liturgical year can enrich the variety of our worship. Therefore, it helps us to have a broader, deeper, and more vital relationship with the living God. It keeps us from the possibility of our worship becoming so routine that we cease to wonder at the grandeur of God. To put it bluntly, the variations of the Christian year help us not to become bored in worship. Bored in worship? Is it possible? Logically speaking, this seems utterly impossible. If we remember that we worship the awesome Creator of the universe, it’s hard to factor boredom into the worship equation. But, sometimes, no matter how wonderful God is, and no matter how truthful our worship might be, if our expressions of worship are virtually the same from week to week, a kind of monotony can set in, and we can become – Heaven forbid! – bored. Perhaps you’ve had the experience of learning a new hymn or worship song and absolutely loving it. As you sing, your mind and heart are truly lifted before God. But, after you’ve sung the same song for the hundredth time, it loses some of its punch. Its tune is still memorable and its lyrics still full of truth, but its power to move your heart and stretch your mind has been diminished.

Worshiping in the same mode every week is a little like driving for a long distance through awesome mountains. When I first see the Rocky Mountains, for example, my heart explodes with joy and awe. These feelings continue for quite a while. But, after I’ve driven among the Rockies for a day or more, I must confess that my appreciation begins to wane just a bit. I no longer remark on the stunning scenery, but begin to take it for granted. Of course the mountains themselves are still as majestic as ever. They haven’t changed or diminished, but my own sensibilities have become dull. I need refreshed vision so I can see the Rockies once again in their awesome beauty.

Worshiping in the same mode every week is a little like driving for a long distance through awesome mountains. When I first see the Rocky Mountains, for example, my heart explodes with joy and awe. These feelings continue for quite a while. But, after I’ve driven among the Rockies for a day or more, I must confess that my appreciation begins to wane just a bit. I no longer remark on the stunning scenery, but begin to take it for granted. Of course the mountains themselves are still as majestic as ever. They haven’t changed or diminished, but my own sensibilities have become dull. I need refreshed vision so I can see the Rockies once again in their awesome beauty.

If, however, my scenic menu were to be varied a bit, I’d be much less likely to become complacent in my admiration of the scenery. A few summers ago, my family and I took a driving trip from Southern California, through the southwestern desert, the rangelands of Utah, and the verdant forests of eastern Idaho. We drove through the varied terrain of Yellowstone National Park and alongside the majestic Grand Tetons. Then we returned by way of the stunning redness of Zion National Park. In over two weeks of travel, I was never bored because my world kept changing. There were always new wonders to behold.

What I’ve just described is analogous to worship in light of the liturgical year. We begin in the rising plain of Advent, which leads us to the top of the celebrative pinnacle of Christmas. Then, after a month of travel through the fertile grasslands of “ordinary time,” we enter the parched desert of Lent in which our thirst for God is magnified. Holy Week guides us through the tortuous geography of Jesus’ last week, culminating in the dark cave of Holy Saturday. On Easter morning, the sun breaks forth with glorious light, and we are filled with awe as we gaze upon the towering mountain of God’s victory over death. Throughout the season of Eastertide, the world seems brighter, more alive than ever before. At Pentecost, we remember the our fellow travelers and refuel to continue on through the rolling hills of ordinary time, until we return to where we began at the start of Advent.

I’ve known Christians who have been uncomfortable with certain aspects of the Christian year. They haven’t liked the waiting of Advent or the focus on our mortality in Lent. They want to live each day as if it were Easter. Now, in a sense, my friends are theologically correct. We should indeed live daily in light of the victory of God in Christ. But, speaking from my own experience, the less obviously celebrative seasons of the church year (Lent, Advent) actually prepare me to experience greater vitality and rejoicing on the great feasts of Christian year, Christmas and Easter. Before I paid much attention to Lent and Holy Week, Easter zipped by without making a major dent in my consciousness. Now, as I keep the seasons of Lent and Holy Week, and as Easter has been stretched to include Eastertide, my joy over the resurrection has been multiplied several times over.

Once again I should emphasize that what I’ve been describing here is not a matter of biblical rule. You don’t have to recognize the Christian year to be a faithful follower of Jesus. But the experience of countless believers throughout the centuries should at least encourage you to consider shaping your yearly life by the themes and narratives of Scripture – and this is, after all, what the Christian year is really all about.

Comments (1)

Hi, Mark, I believe if we class ourselves in the image of Christ and the church represents Him then to follow the liturgical year is of vital importance.

The church I am attending (not physically at the moment) does not see the importance of this and runs with his own schedule.

To me the church is lifeless. It saddens me to see this happening.

I live in a small country town in Australia. I loved your informative article on the liturgical year so thank you.