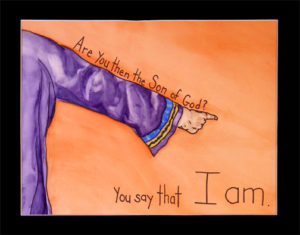

The Third Station: Jesus is Condemned by the Sanhedrin

When day came, the assembly of the elders of the people, both chief priests and scribes, gathered together, and they brought him to their council. They said, “If you are the Messiah, tell us.” He replied, “If I tell you, you will not believe; and if I question you, you will not answer. But from now on the Son of Man will be seated at the right hand of the power of God.” All of them asked, “Are you, then, the Son of God?” He said to them, “You say that I am.” Then they said, “What further testimony do we need? We have heard it ourselves from his own lips!”

Luke 22:66-71

Painting © Linda E.S. Roberts, 2007. For permission to use this picture, contact Mark D. Roberts.

According to Jewish law, it was wrong to try a criminal in the night. So, properly, those who accused Jesus waited until dawn, when the “assembly” or “council” could legally gather (the “council” is, more literally, the “Sanhedrin”). The leaders of the council, which was moderated by the high priest, wanted to know if Jesus claimed to be the Messiah. For them, this would be tantamount to a revolutionary claim, exactly the sort of thing that got the Jews into major trouble with Rome. False messiahs led to nothing but heartache and suffering for the Jewish people.

Given Jesus’s failure to raise up an army capable of setting Judea free from the Romans, there would have been little reason for the members of the Sanhedrin to believe that he was the true messiah. He didn’t fit the bill, as far as they were concerned. This may help to explain Jesus’s strange reticence with respect to his messiahship. Nowhere in the Gospels does he ever say, outright, “I am the Messiah.” Only in the Gospel of Mark does Jesus admit plainly to being the Messiah (Mark 14:62), but even there he quickly changes the subject to focus on the Son of Man seated at the right hand of God. Jesus knew that his peers would have misunderstood a claim to messiahship as a proclamation of revolution and the re-establishment of a Jewish kingdom. That’s what people expected of the true Messiah. Of course Jesus didn’t deny that he was the Messiah either, something that might have allowed him to be released by the Sanhedrin with only a severe beating. His failure to say that he was not the Messiah, combined with his cryptic, “You say that I am,” was enough to convince the Sanhedrin of Jesus’s guilt.

What was his crime? What had he done that was worthy of death? For one thing, only days earlier Jesus had made a mess of the temple, interrupting its sacrifices and labeling it as a “den of robbers,” a phrase Jesus borrowed from Jeremiah in one of the ancient prophet’s predictions of the temple’s demise. By speaking so negatively of the temple, Jesus was seen by the Jewish officials to be speaking negatively of God himself. The temple was, after all, the house of God, the place where God had chosen to dwell. Thus, by speaking poorly of the temple, Jesus was believed to have been blaspheming God.

Moreover, in his trial, Jesus not only wouldn’t reject his messiahship, but he also claimed that he would be “seated at the right hand of the power of God” as the promised Son of Man (Luke 22:69). This was perceived by the council, beginning with the high priest, as blasphemy and clear evidence of Jesus’s guilt. But making this claim wouldn’t have been a crime if Jesus were telling the truth. In the minds of the members of the Sanhedrin, however, there was no possibility of Jesus actually being the Son of Man who would share in God’s own power and glory. Sure, he could do a few miracles. But usher in the divine kingdom? Hardly. So the rabble-rouser, temple-destroyer, and all-around troublemaker was now, as far as the Sanhedrin was concerned, an obvious blasphemer. (Not all members of the Sanhedrin agreed that Jesus was guilty and worthy of death. Joseph of Arimathea, for example, “had not agreed to their plan and action” [Luke 23:51].)

Have you ever wondered why Jesus wasn’t clearer about who he was and what he had come to do? I certainly have. It seems like it would have been so much easier for all, including those of us who seek to follow Jesus today, if he had only said, “Yes, I am the Messiah, but not in the sense you expect. I have been anointed by God to bring the kingdom, but not in a military-political way. The kingdom is coming through transformed hearts, communities, and cultures. Most of all, the kingdom is coming through my death, as I bear the sin of Israel, and, indeed, the sin of the world. As Messiah, I must also suffer in the role of Isaiah’s Servant.” Yet Jesus didn’t say this directly. It’s something we have to piece together from his words and deeds.

And we, like the people of his day, even his disciples, often get things confused. We rightly reject the notion of Jesus as a military-political Messiah. But then we tend to limit his saving work to post-mortem Heaven for individual believers, rather than transformation of the whole cosmos, beginning with our world today, including the world of work. We don’t make the connection between Jesus as the Messiah and the prayer he taught us: “Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.”

When we confess Jesus as Christ or Messiah, we’re acknowledging him as our personal Savior. (“Christ” is an English variation of the Greek word christos, which is equivalent to the Hebrew mashiach, or “messiah.” They all mean, “anointed one.”) But we’re saying more than this. We’re also recognizing that he came to inaugurate the kingdom of God. Though this kingdom won’t fully come until Jesus himself brings it, we get to share in the blessings and responsibilities of the kingdom even now. Our calling as followers of Jesus is to do the works of the kingdom, so that the reign of God might invade this world. We do these works wherever God has placed us: in our neighborhoods, our families, our churches, our offices, our stores, our friendship groups, and so forth.

At the same time, we recognize that God’s kingdom isn’t completely present in our lives, and we look forward to the day when all will be fulfilled. Then, in the classic words of Revelation 11:15, put to such wonderful music in Handel’s Messiah, we’ll celebrate the fact that: “The kingdom of this world is become, The kingdom of our Lord, and of His Christ, And He shall reign forever and ever. Hallelujah!”

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

When you think of Jesus as the Messiah, what images or ideas come to mind?

Why do you think Jesus was so guarded when talking about himself as the Messiah?

In what ways do you experience the kingdom of God in your life? What about in your work?

PRAYER:

Gracious Lord Jesus, the Jewish officials didn’t understand what it meant for you to be Messiah and they condemned you as a criminal worthy of death. Your own followers didn’t understand what it meant for you to be Messiah, so they scattered and hid in your hour of crisis. Help me not to be like these!

Help me to understand what it means when I confess you to be the Christ, the Messiah, the Anointed of God. And may this confession lead me to a life of true discipleship. Let your kingdom come, Lord, and your will be done, on earth as in heaven. And let this happen in every part of my life, even today! Amen.

Explore more at the Theology of Work Project online commentary: Joseph of Arimathea

Mark D. Roberts

Senior Fellow

Dr. Mark D. Roberts is a Senior Fellow for Fuller’s Max De Pree Center for Leadership, where he focuses on the spiritual development and thriving of leaders. He is the principal writer of the daily devotional, Life for Leaders, and t...