Will I Be Remembered After I’m Gone? Does It Matter?

This article was inspired by two experiences I had last month, one in Vermont and the other in Massachusetts. Both experiences got me wondering: Will I be remembered after I’m gone? And does it matter?

A Covered Bridge in Vermont

The first experience happened just outside of Woodstock, Vermont. I was there to pick up my wife, Linda, who had been leading a retreat nearby. As I was driving along a country road, I spied a covered bridge. Instantly I felt a powerful compulsion to pull off the road and check out the bridge. (In case you’re wondering, it was the Lincoln Bridge, built in 1877 over the Ottauquechee River. See photo.)

Why did I feel such a strong desire to inspect that covered bridge? For one thing, I do enjoy a covered bridge’s mix of human ingenuity, historic quaintness, and natural beauty. Plus, I don’t get to see covered bridges very often. We have only a few in California; little Vermont, by contrast, has over 100. But enjoyment and novelty were not the main reasons I pulled off the road. My reason was much more personal. You see, my mother loved covered bridges. I have fond memories of childhood travels in Vermont with my family, using maps and guidebooks to find what seemed like every covered bridge in the state. Each time we discovered a new one, my mother would cheer with joy and we’d stop to check out the bridge. So, when I saw a covered bridge in Vermont last month, sweet memories of my mother filled my heart and compelled me to stop. Plus, it was Mother’s Day! I could think of no better way to remember my mother than to savor a covered bridge in her honor.

Why did I feel such a strong desire to inspect that covered bridge? For one thing, I do enjoy a covered bridge’s mix of human ingenuity, historic quaintness, and natural beauty. Plus, I don’t get to see covered bridges very often. We have only a few in California; little Vermont, by contrast, has over 100. But enjoyment and novelty were not the main reasons I pulled off the road. My reason was much more personal. You see, my mother loved covered bridges. I have fond memories of childhood travels in Vermont with my family, using maps and guidebooks to find what seemed like every covered bridge in the state. Each time we discovered a new one, my mother would cheer with joy and we’d stop to check out the bridge. So, when I saw a covered bridge in Vermont last month, sweet memories of my mother filled my heart and compelled me to stop. Plus, it was Mother’s Day! I could think of no better way to remember my mother than to savor a covered bridge in her honor.

After I returned to my car and drove away, I wondered if someday my children might see something that reminded them of me such that they might stop for a moment of remembrance. If so, what would that be? As I continued to reflect, I asked myself, “Will I be remembered after I’m gone?”

Harvard Yard

Shortly after my covered bridge encounter in Vermont, my family and I gathered in Cambridge, Massachusetts for my son’s graduation. He was graduating with a Ph.D. from what is now called the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Mr. Griffin, who has given over a half-billion dollars to Harvard, will forever have his name associated with what we used to call the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS). Griffin’s name will be known, that’s for sure. But, besides his name, will he be remembered after he’s gone? (He’s only 54 years old, by the way.)

Shortly after my covered bridge encounter in Vermont, my family and I gathered in Cambridge, Massachusetts for my son’s graduation. He was graduating with a Ph.D. from what is now called the Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Mr. Griffin, who has given over a half-billion dollars to Harvard, will forever have his name associated with what we used to call the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS). Griffin’s name will be known, that’s for sure. But, besides his name, will he be remembered after he’s gone? (He’s only 54 years old, by the way.)

Though buildings, gates, rooms, professorships, academic centers, and even whole schools at Harvard are named after people, I wouldn’t say that the people they honor are generally remembered. For example, I spent my freshman year in Straus Hall, though with no inkling of why it bore that name (see photo). Years later, I learned that the sons of Isidor and Ida Blun Straus donated my freshman dorm to Harvard in honor of their parents, who had once owned Macy’s Department Store in New York and who died in the sinking of the Titanic. Harvard Yard’s most prominent building, Widener Library, was also funded in memory of a Titanic victim, Harry Elkins Widener. But I wouldn’t say we remember Harry the person even though his name is emblazoned all over the university.

Though buildings, gates, rooms, professorships, academic centers, and even whole schools at Harvard are named after people, I wouldn’t say that the people they honor are generally remembered. For example, I spent my freshman year in Straus Hall, though with no inkling of why it bore that name (see photo). Years later, I learned that the sons of Isidor and Ida Blun Straus donated my freshman dorm to Harvard in honor of their parents, who had once owned Macy’s Department Store in New York and who died in the sinking of the Titanic. Harvard Yard’s most prominent building, Widener Library, was also funded in memory of a Titanic victim, Harry Elkins Widener. But I wouldn’t say we remember Harry the person even though his name is emblazoned all over the university.

If I had the financial means and motivation – which I don’t, by the way – I could probably get some institution to name something after me. But would that mean I’d be remembered after I’m gone?

Why Do We Want to Be Remembered?

Since returning from my recent trip to New England, I’ve been contemplating the issue of post-mortem remembrance. If you were to ask people, “Do you want to be remembered after you’re gone?” I imagine you’d almost always get a positive response. I’d answer that question affirmatively and I expect you would too. Those of us in the third third of life tend to be more aware of this desire because we’re generally closer to the “after you’re gone” reality. But, I wonder, why do we want to be remembered? Why does this matter to us?

Moreover, should it matter to us? Is seeking to be remembered post-mortem actually something worth living for now? Or should our efforts be directed differently?

Before I offer some thoughts in response to these questions, you may want to pause for a few moments of personal reflection. Think about it. Do you want to be remembered after you’re gone? If so, why? If not, why not? Does post-mortem remembrance really matter to you? If so, how much does it matter?

Scholarly Input on “The Desire to be Remembered”

As I was musing about being remembered after death, I looked for what scholars have to say about this. It turns out they have relatively little to say. But, very recently, three scholars from the University of Otago in New Zealand hit the bullseye of my curiosity: “The desire to be remembered: A review and analysis of legacy motivations and behaviors” (New Ideas in Psychology 69 [April 2023]). Brett Waggoner, Jesse M. Bering, and Jamin Halberstadt begin by noting the absence of scholarly interest in this question, “The psychological motivations and mechanisms underlying a desire to be remembered after death is an understudied area in the social sciences.”

Then, drawing from a wide spectrum of academic approaches, the authors propose a variety of perspectives on why people want to be remembered after they’re gone. These include the need to be loved and to belong, likely adaptive benefits of legacy, death anxiety and symbolic immortality, narrative and the self as story, and imagining a selfless future. The authors conclude, “Legacies are likely appealing because they help us to transcend death, provide a purpose and satisfying ending to one’s life story, and/or recruit intuitive, but flawed, cognitive mechanisms for envisioning the self in a world where it will no longer exist.”

Then, drawing from a wide spectrum of academic approaches, the authors propose a variety of perspectives on why people want to be remembered after they’re gone. These include the need to be loved and to belong, likely adaptive benefits of legacy, death anxiety and symbolic immortality, narrative and the self as story, and imagining a selfless future. The authors conclude, “Legacies are likely appealing because they help us to transcend death, provide a purpose and satisfying ending to one’s life story, and/or recruit intuitive, but flawed, cognitive mechanisms for envisioning the self in a world where it will no longer exist.”

In “The desire to be remembered,” there is a curious conflation of legacy as “something transmitted by or received from an ancestor or predecessor or from the past” and legacy as being remembered positively after death. This conflation is intentional. The authors explain, “Legacy centers, rather curiously, on the reputation of the self after death. It is primarily this aspect of legacy (how others will regard the self once that self ceases to exist, and why this is of particular concern to the living) that we examine in the present article.”

Do I Really Want to Be Remembered After I Die?

I agree with Waggoner, Bering, and Halberstadt that people often think of legacy not just as what we leave for the next generation(s), but also as how we are regarded by them. But I’m inclined to believe that the conflation of legacy as making a difference and legacy as being remembered may not be helpful, not only to scholars but also to those of us who want to flourish in the third third of life.

Now, let me be very clear. Like most people I know, especially older adults, I do want to be remembered favorably when I’m gone. Why? Because this means that I have made a difference to people in my life. It shows that I have mattered in the lives of other human beings. It’s evidence that I loved others who loved me. (What I’m talking about is covered by Waggoner, Bering, and Halberstadt in their section on “narrative and the self as story.”) If, after my death, nobody ever remembered me, that would strongly suggest that I had not lived in the way I intended to live, building relationships with people that led to both joy and flourishing.

I do not believe I need to be remembered by crowds of people for my life to have mattered. Yes, I do hope those who are close to me remember me with gratitude: my family, my friends, my colleagues, my mentees, etc. But I have absolutely no need for my name to be emblazoned on buildings, known by people with whom I have had no relationship. I’m not saying it’s wrong for others to seek this if they wish. It’s just not something that makes a difference to me.

Similarly, I don’t need to be remembered by more than a couple of generations of my relatives, friends, and associates. Yes, I would like my children to remember me when I’m gone and, if I end up with some grandchildren, their remembrance of me would be nice, too. I hope those with whom I have worked closely will, upon occasion, think of me because this suggests I made a positive difference in their life. But if, for example, the De Pree Center is thriving in thirty years, I don’t need anyone working here to remember my name or my contribution to the center’s life. The thought that the De Pree Center will still be serving people well gives me joy, not my being remembered when I’m gone. My legacy is about what I have invested in the Center, its work, and its people. My legacy is not about being remembered for this work three decades from now.

Legacy as Passing On the Essence of One’s Self

So, yes, I’d like to be remembered when I’m gone. But that’s not central to my sense of my own legacy. Now, I recognize that Waggoner, Bering, and Halberstadt claim that legacy is often talked about as a combination of what we pass down to the next generations and how we are remembered by them. But I believe this combination, however common it might be, is not particularly helpful. I’d rather keep legacy and remembrance separate.

Consider the case of my children, for example. Yes, I do want them to remember me fondly when I’m gone. But, far more than this, I want them to be the kind of people I have labored for them to become. I want them to be thoughtful, kind, and gracious. I want them to use their gifts and talents well to make a positive difference in the world. I want them to know and trust God. I want them to be faithful and committed in their core relationships. I want them to care for people who are often ignored or excluded. These are some of the things I have tried to pass on to them. And, I should note, they are qualities I see in my grown children already. In fact, when it comes to many of the things I care most about, my children have already surpassed their father’s legacy hopes for them.

Gerontology professor Elizabeth G. Hunter did some fascinating research related to legacy. In “Beyond Death: Inheriting the Past and Giving to the Future,” she focused on “legacy as a component of aging experience among women.” As she listened to the life narratives of a variety of women, she found this: “Through the stories of the participants in this study, legacy emerges as a means of passing on the essence of one’s self, in particular one’s values and beliefs. Legacy is a method of leaving something behind after death and making meaning of the end of life.” Legacy, in Hunter’s research, wasn’t about being remembered so much as it was passing on what matters most to the next generation. Legacy has to do with “the desire to help future generations make a mark of their own and to pass along hard won knowledge, values and beliefs—wisdom.” As older adults do this, we are “making meaning” of our lives. We are composing personal narratives that tell the story of how and why our lives have mattered.

Hunter’s work helps me to clarify my own longings for legacy. Yes, as I’ve said before, I do want to be remembered by those who are close to me as evidence that I’ve made a difference in their lives. But, far more than this, I hope that I will have passed on to others the things I care most about in the world, my “hard won knowledge, values and beliefs,” yes, even my “wisdom.”

Legacy and My Great-Grandfather

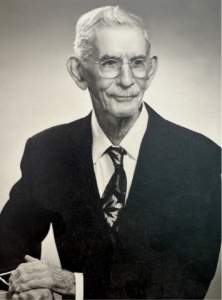

I met my great-grandfather one time. I was very young. He was very old. That’s what I remember most about our meeting. He had white hair, lots of wrinkles, and a cane (which lives now in my entry hall). My great-grandfather died shortly after our meeting at the age of 93. I was almost 3.

I can’t say I remember my great-grandfather in the way some people talk about legacy. I didn’t know him well. But I believe that, in many ways, I am part of his legacy. I’m not referring to post-mortem remembrance but to the passing down of knowledge, values, beliefs, and wisdom.

Consider this. My great-grandfather, whose name was Manly (!), cared deeply about education. Though he grew up on a farm in Wisconsin, he became a teacher in California, then a principal, and finally the President of the Los Angeles Board of Education. Several of his children became educators, as did many of his grandchildren, his great-grandchildren (including me and my siblings), and his great-great-grandchildren (my children). Though I never heard Manly speak about teaching, he passed down his commitment to education in a myriad of ways in our family.

Consider this. My great-grandfather, whose name was Manly (!), cared deeply about education. Though he grew up on a farm in Wisconsin, he became a teacher in California, then a principal, and finally the President of the Los Angeles Board of Education. Several of his children became educators, as did many of his grandchildren, his great-grandchildren (including me and my siblings), and his great-great-grandchildren (my children). Though I never heard Manly speak about teaching, he passed down his commitment to education in a myriad of ways in our family.

My children, Nathan and Kara, have no memory of their great-great-grandfather, other than what I’ve told them. But they do share some of his most deeply held convictions and values. I don’t think this is a coincidence. It’s a vital part of Manly Williams’s legacy. He may not be remembered by my children, but his legacy is alive in them.

Ironically, in this season of life, I often think of my great-grandfather almost every week when I’m in worship. Why? Because I’m now part of the church that Manly and his wife, Josephine, attended for 58 years. I sit in the same pews where they sat for decades, doing what they did week after week, namely worshipping God in song, prayer, and Bible-based learning. An essential part of Manly’s legacy, passed on to me through my grandfather and my mother, is a deep commitment to Jesus Christ. Given how my great-grandfather lived his life, I’m guessing that he would be more pleased by the fact that I am worshipping God than by the fact that I sometimes remember him when I worship.

Conclusion: What Do You Think?

To sum up, though I believe people—including me—do want to be remembered after we’re gone, and that’s just fine, I don’t believe this is the most important thing about our legacy. Legacy has more to do with what we pass on the others, things both material and immaterial. In particular, the legacy that matters most involves passing on our “hard won knowledge, values and beliefs—wisdom,” to quote once again from Elizabeth Hunter. If we focus on this quality of legacy, not only will we leave behind something that matters, but it’s likely that we will be remembered well. I want to live to make a meaningful difference in the lives of others and the wider world. Post-mortem remembrance may come as a byproduct of this effort.

What I’ve written in this article isn’t meant to be the final word on matters of post-mortem remembrance and legacy. Rather, this is my first attempt to sort out some things I’ve been pondering. I’d love to know your thoughts about what I’ve written. You can email them to me personally at [email protected]. Or you can add public comments at the bottom of this article on our website.

I’m sure I’ll have more to say about this issue in the future, perhaps in next month’s edition of Third Third Life. So, stay tuned. And thanks for walking with me on this journey of third third discovery.

Banner image by Corwin Thiessan on Unsplash.

Mark D. Roberts

Senior Fellow

Dr. Mark D. Roberts is a Senior Fellow for Fuller’s Max De Pree Center for Leadership, where he focuses on the spiritual development and thriving of leaders. He is the principal writer of the daily devotional, Life for Leaders, and t...

Comments (1)

I found this essay while searching about something only recently heard: The Egyptian Pharaohs (and other leaders) built the great monuments (pyramids, etc.) BECAUSE they believed they had to be remembered in order to achieve life after death. This was a new idea to me, and I suspect it to be one lie of the Devil. Maybe it is behind the medieval legacies, to continue to pray for the King after he is gone. Maybe it continues to this day with the named memorial buildings, churches, colleges, programs, etc. Surely, the only one who needs to remember me after I die (and the only One likely) is God?